ESSAY

ESSAY

7 Days in Cuba

July

1997

by David Speranza

(photos by the author)

Cuba has generated more than its share of news

lately. What with hotel bombings, jailed reporters, violations of the

U.S. trade embargo, the Pope’s January visit, and periodic reports of

Fidel Castro’s long-awaited death, the tiny Caribbean nation seems to

be entering a new period of turmoil in its much-troubled history.

But along with so much unrest, the country has been attracting

something else: tourists. In fact, tourism has become the nation’s

leading industry. Americans, of course, are more or less forbidden by

the U.S. government from traveling or spending money there (I went by

way of Canada). But for those vacationers fortunate enough to visit

this neglected Caribbean nation, the rewards go beyond a good tan and

pockets full of unusually white sand.

For many travelers, even outside the U.S., Cuba remains something of a

mystery. Its former tug-of-war status between the United States and the

Soviet Union—with Fidel Castro as shrill, bearded referee—has long

painted it as inhospitable to visitors from more developed nations.

Even today, six years after the Soviets closed up shop, American

policymakers continue to portray Cuba as nothing short of Hades, and

Castro as the devil himself.

But the world has changed since 1989, something the U.S. State

Department, even under Clinton, doesn’t seem to fully understand. With

communism no longer a world threat, tiny Cuba, once a fearsome conduit

of Soviet arms and ideology, has been cut adrift, its commitment to

communism seeming less a threat than the quirky preference of an aged,

stubborn leader too proud to realize history has passed him by. But

give Fidel credit: He has

tried to loosen the reigns a little. With the Soviets no longer the

country’s primary trading partner, he’s been forced to take such

unrevolutionary steps as allowing his citizens to possess U.S.

currency, and even (with limitations) go into business for themselves.

Canadians and Europeans already know this. They’ve been visiting the

island—and in the last year or so, investing in it—for some time. And

they’re more than happy to ignore the U.S. grudge against Castro,

positioning themselves for the day when the Bearded One passes on and

America is left playing economic catch-up.

But while the western powers bump elbows in preparation for

that fateful day, there remain any number of pleasures vacationers can

take on Cuba’s tropical shores. Aside from the usual

activities—sunbathing, surfing, diving, spelunking—what separates this

country from other Caribbean vacation spots are its unspoiled lands and

its poignant sense of history. It’s hard not to be moved by the sense

of world events impacting on daily lives here, beyond the rhetoric of

ideology and politicians trying to prove whose system is right.

This

was apparent soon after I stepped onto the baked tarmac of the tiny

airport in Varadero and breathed in the thick, moist July air. As my

traveling companion and I hitched a ride on a tour bus to the center of

town, what struck me most weren’t the palm trees, the ocean, or the

banana fields—all of which I’d expected—but rather the complete absence

of billboards for McDonald's, Marlboro, or Coke. It made complete sense

given the harshness of U.S. policy, but it was odd not having those

ubiquitous beacons of capitalism greeting us as we left the airport.

For once I truly felt I was "getting away from it all." (Though we

later discovered that Coke, and even Marlboro, are

available in Cuba—they're simply not advertised. The Cokes came from

Mexico; no telling where the Marlboros came from.)

This

was apparent soon after I stepped onto the baked tarmac of the tiny

airport in Varadero and breathed in the thick, moist July air. As my

traveling companion and I hitched a ride on a tour bus to the center of

town, what struck me most weren’t the palm trees, the ocean, or the

banana fields—all of which I’d expected—but rather the complete absence

of billboards for McDonald's, Marlboro, or Coke. It made complete sense

given the harshness of U.S. policy, but it was odd not having those

ubiquitous beacons of capitalism greeting us as we left the airport.

For once I truly felt I was "getting away from it all." (Though we

later discovered that Coke, and even Marlboro, are

available in Cuba—they're simply not advertised. The Cokes came from

Mexico; no telling where the Marlboros came from.)

Varadero’s beaches, as the guide books promised, were

beautiful—white sand, warm emerald waters, placid waves—though not as

well maintained as, say, Mexico's (the lack of Coke signs was more than

made up for by the many crushed soda cans littering the sand). But

aside from the beaches, there was surprisingly little of note in

Varadero. It's a resort town, in many ways like other resort towns only

a bit more rundown. In fact, much of it is indistinguishable from parts

of first world and other developing countries. Aside from the scarcity

of billboards (and the terrible waiters), you'd hardly know it was

communist.

Most of what caught my eye in Varadero were the small, incongruous

touches: the oil derricks pumping rhythmically into the earth just

outside town; the lone smokestack to the west spewing flames into the

atmosphere, causing nighttime clouds to throb orange from within and

the air to reek of sulfur; the large set of rusting bleachers

dominating an entire block along the main street—presumably in

anticipation of some state-sponsored parade; the hotel TVs, most of

whose channels were devoted to English-language (and usually American)

programming—CNN, VH-1, HBO, etc.—in a country spurned by America; the

families of Cubans visible through the open windows and doors of their

houses at night, rooted to their living rooms by the gray glow of a

television, a single (surplus?) family member seated outside, gazing in

through a window or door, equally transfixed, equally unmoving.

And the cars.

Cuba's cars, if they aren't already legendary, should be. The

country is crawling with vintage American monsters from the 1940s and

'50s: great bloated finned things with steering wheels the size of

tires and rear lights poking up on stalks like the eyes of a great tin

lobster. Beautiful extinct beasts inhabiting a Detroit version of

Jurassic Park.

Besides their number (you'll see at least one on every block),

what makes them so intriguing is how lived-in they are. These are not

the gleaming, spit-polished, Turtle-Waxed museum pieces glimpsed in

period films or car shows; these are cars that have been used nearly

every day since first rolling off the production line. They're

battered, they're rusting, they've got holes punched in their sides,

windows cracked, and many have more layers of paint on them than the

ceiling of a Brooklyn brownstone.

Of course, there are exceptions—cars which their owners take

more than customary pride in, and which (more importantly)

they can afford

to keep in decent shape. But even these retain the air of

something functional as opposed to decorative: you sense they've been

passed down from one generation to the next with loving care. But

polished or rusting, the sight of a two-toned Buick lumbering around a

corner never fails to draw appreciative gasps from even the most jaded

foreign visitor.

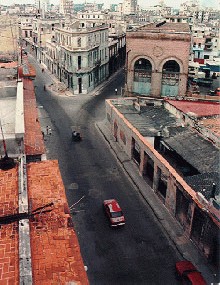

After three days of

tanning in Varadero, we decided to take a bus to Havana—a city that’s

seen better days. Though touted as the greatest repository of preserved

Spanish colonial architecture in Latin America, the problem starts with

how one defines “preserved.” Yes, the city is a veritable museum of

18th and 19th century buildings. But only if you mean a museum that's

been bombed. Communism never looked so bad. According to my fellow

traveler, who works in war-ravaged Bosnia, the city appears in worse

shape than Sarajevo. Buildings and streets are crumbling

everywhere you turn, leaving the  whole

of Central Havana looking like a dingy gray skeleton or piles of

broken, poorly cleaned teeth. Reportedly 300 or so buildings collapse

of their own accord each year, and the streets contain enough rubble to

prove it. When democracy finally does come to Cuba, someone's going to

make a hell of a lot of money

whole

of Central Havana looking like a dingy gray skeleton or piles of

broken, poorly cleaned teeth. Reportedly 300 or so buildings collapse

of their own accord each year, and the streets contain enough rubble to

prove it. When democracy finally does come to Cuba, someone's going to

make a hell of a lot of money selling paint.

selling paint.

Yet the occasional restored gem does pop up, especially in Old Havana,

a small, tourist-oriented district which seems to have garnered the

bulk of the city's restoration funds. There are churches and parks and

restaurants and museums (including a car museum)—even a privatized

outdoor market set inside a large cobbled square—all looking as spiffed

up as any you'll find in the developing world.

But in the less fortunate areas—i.e., most of the city center—the only

hope for restoration seems to come in the form of the scattered private

businesses allowed to operate in Cuba since 1993. The most promising of

these are the paladars—privately

owned restaurants, usually based in someone's home and allowed to seat

no more than 12 guests at a time (thus ensuring less competition for

the state-owned restaurants). Despite this handicap, these tiny establishments are

flourishing. One that my travelmate and I dined at was located on a

second-floor balcony overlooking Havana’s glittering harbor, and though

it only had two tables, it stood out from the many crumbling buildings

around it by virtue of its painted and restored facade. The walls were

mended, the glass replaced, the paint freshened—making it a tiny

capitalistic oasis in a sea of fading communism. Not only was the meal

excellent, it was cheaper than most of those we ate elsewhere.

According to the owner, a patient, cheerful woman of African descent,

the place has been doing excellent business since opening two years

ago. And though I forgot to ask, I wouldn't be surprised if the

adjoining building, also restored, belonged to her as well.

restaurants). Despite this handicap, these tiny establishments are

flourishing. One that my travelmate and I dined at was located on a

second-floor balcony overlooking Havana’s glittering harbor, and though

it only had two tables, it stood out from the many crumbling buildings

around it by virtue of its painted and restored facade. The walls were

mended, the glass replaced, the paint freshened—making it a tiny

capitalistic oasis in a sea of fading communism. Not only was the meal

excellent, it was cheaper than most of those we ate elsewhere.

According to the owner, a patient, cheerful woman of African descent,

the place has been doing excellent business since opening two years

ago. And though I forgot to ask, I wouldn't be surprised if the

adjoining building, also restored, belonged to her as well.

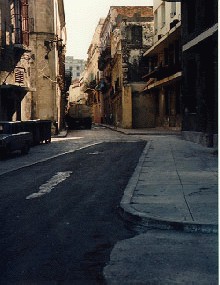

Our first night in Havana included a lengthy walk through the city's

humid center, exploring many a darkened nook and cranny. Central

Havana's basic design seems to consist of densely packed, crumbling

buildings whose rusted terraces continually threaten to drop onto the

wide, poorly lit streets below. These streets may be no wider than the

average North American street, but because of the small number of

parked vehicles along their curbs, they seemed unusually large. More

prominent than the occasional car were the occasional trash dumpster

and occasional pile of rubble.

And the Cubans, of course: seated bodies inhabiting doorways and street

corners, mostly young men with nothing better to do and no cooler place

to do it; visible in patches beneath murky shadows, almost subliminal,

until suddenly one grins and calls out to you, holding both hands out

in front of him as if measuring something, but in fact indicating a

desire to sell cigars. And the families: visible along nearly every

street, inert within their first-floor apartments, in requisite groups

of three or four and, just as in Varadero, perched before their

televisions, a stray neighbor or relative peering in from outside.

Windows, curtains, and doors seemed nonexistent, replaced by

elaborately wrought iron gratings more reminiscent of cafe or

restaurant decor than someone's home. The family dogs lurked just on

the fringes, in alleys and doorways—scrawny mongrels no bigger than

inbreeding and nutrition would allow. Friendly and passive, they seemed

to bark more from boredom and heat than anything else.

Havana

is a truly surreal place, like something Rod Serling might have cooked

up during an especially vivid fever dream. Its streets seem filled with

rejects and castoffs from the rest of the world, like a great dumping

ground for obsolete consumer goods—as if an entire city had been

outfitted at an international rummage sale. The range of periods and

technologies visible on any street corner would actually be charming if

it wasn't the product of such a diseased system. BothSpanish ballads

and Western disco blare for attention from plastic, tinny speakers

perched amid parrot-decorated cafes, while massive 1950's

automobiles—some gleaming, others coughing their last—pass in front of

Spanish colonial buildings, blocky communist hotels, and even a

Havana

is a truly surreal place, like something Rod Serling might have cooked

up during an especially vivid fever dream. Its streets seem filled with

rejects and castoffs from the rest of the world, like a great dumping

ground for obsolete consumer goods—as if an entire city had been

outfitted at an international rummage sale. The range of periods and

technologies visible on any street corner would actually be charming if

it wasn't the product of such a diseased system. BothSpanish ballads

and Western disco blare for attention from plastic, tinny speakers

perched amid parrot-decorated cafes, while massive 1950's

automobiles—some gleaming, others coughing their last—pass in front of

Spanish colonial buildings, blocky communist hotels, and even a near-duplicate of the U.S. Capitol. The wheeled conveyances

alone are enough to make one blink: along with the already mentioned

American relics, there are British Vauxhalls, Russian Ladas, Czech

Skodas, Polish Fiats, and a strange variety of six-doored taxicab,

possibly from South America. Equally numerous are the fleets of

heavy-fendered bicycles, rickshaw-style pedicabs, and a shocking number

of motorcycles with sidecars, including some pre-communist Czech Jawas.

near-duplicate of the U.S. Capitol. The wheeled conveyances

alone are enough to make one blink: along with the already mentioned

American relics, there are British Vauxhalls, Russian Ladas, Czech

Skodas, Polish Fiats, and a strange variety of six-doored taxicab,

possibly from South America. Equally numerous are the fleets of

heavy-fendered bicycles, rickshaw-style pedicabs, and a shocking number

of motorcycles with sidecars, including some pre-communist Czech Jawas.

Probably the most bizarre vehicles are Havana's public buses, huge

diesel-spewing creatures called Camels. These look nothing like the

popular conception of a bus, comprised as they are of two parts: the

front section, identical to the tractor part of a tractor trailer, and

the back, or “trailer” section, a long, boxy carton humped on both ends

and dipping in the middle (thus the name “Camel”). Most of the time

these people-carriers are packed with an alarming number of passengers,

all appearing quite uncomfortable, squinched up against each other and

looking desperate to be somewhere else. I can only imagine the levels

of heat and carbon dioxide stewing inside those rumbling beasts.

The people themselves (66% Spanish, 22% mulatto, 11% black, 1%

Chinese), seemed quite friendly, with no apparent malice towards evil

imperialist Americans. In fact, many appeared pleased to hear where I

was from, usually countering with, "I have a brother/sister/uncle

living in Miami/New York/Tennessee." But most of our conversations with

Cubans usually involved four basic variations:

"Taxi?"

"Cigars?"

"Where you from?"

"Italiano? Francais?"

That is, unless they were kids, in which case the standard salutation

was a snake-like "Tss!" Which translated as: "Turn around so I can

grope you and ask for money."

That was how most of our conversations started. This is how they ended:

"No thanks, we want to walk."

"Gracias, no."

"No Italiano. Canadian. American."

"We've already got cigars, thanks."

"No moleste, por favor."

The 'moleste'

became especially acute whenever I went out with a camera dangling

around my neck. No dummies, these Cubans.

As we walked, we found that shops in the more commercial blocks ranged

from vacant and ghostly to vibrant and adequately stocked, depending on

the level of tourism in the area. The less touristed streets seemed the

epitome of bare-shelved communist chic, the goods on display continuing

the hand-me-down tradition of the city's vehicles. The shelves of one

rather sparse shop window offered the following merchandise to whet

one’s appetite: a hair dryer, three or four portable tape decks, a can

of shoe polish, hairpins, portable clocks, and a large plastic bottle

of some clear blue fluid (ammonia? liquid Drano? radiator fluid? I

certainly couldn't tell). I also couldn't tell if the items were new,

used, or simply permanent display items never intended to be sold.

Both strange and fascinating, Cuba’s contradictions seem to extend from

the streets into the very hearts of the people. A young woman who, with

a friend, commandeered us into an acquaintance's paladar (which was

decorated in a beautiful handmade bamboo motif), claimed she hated

Castro because of the changes he'd been making, i.e., allowing dribs

and drabs of private enterprise into the country in an effort to boost

the nation's economy. Her gripe, aside from an increase in crime and

prostitution, was that everything was becoming "dollars, dollars,

dollars." And yet, at meal's end, when we discovered we'd been

seriously overcharged and didn't have enough U.S. dollars to pay the

bill, this woman was the most adamant one there in making sure we paid

in full. We eventually had to cover the difference with Canadian

dollars, to a stream of apologies from the cook.

After our third day in Havana, we headed back to Varadero for a final

24 hours of touching up our tans, trying out a new hotel, and wading in

that soothing emerald sea. With all the walking, heat, and heavy food

(Cuban cuisine is meat-based, and nothing remarkable), it ended up

being a far more exhausting trip than either of us planned. But it was

worth it, if only for our glimpse of a country on the verge of its

biggest tranformation in nearly 40 years. It’s incredible to think of

the untapped potential of that little island—like Central Europe just

before the doors blew open in 1989. Although if Havana is any

indication, Cuba is in far worse shape than even the worst-off former

eastern bloc nation.

Someday, perhaps soon, a lot of people are going to make a lot of money

in Cuba—and from more than selling paint. And while the prospect of a

democratic Cuba is exciting in terms of the nation’s eventual

restoration by capitalism's hands, it's also a little depressing.

Despite the obvious rewards a market economy can offer, does the world

really need more roadsides cluttered with billboards for McDonald's,

Marlboro, and Coke?